Endling

by Blaize M. Kaye

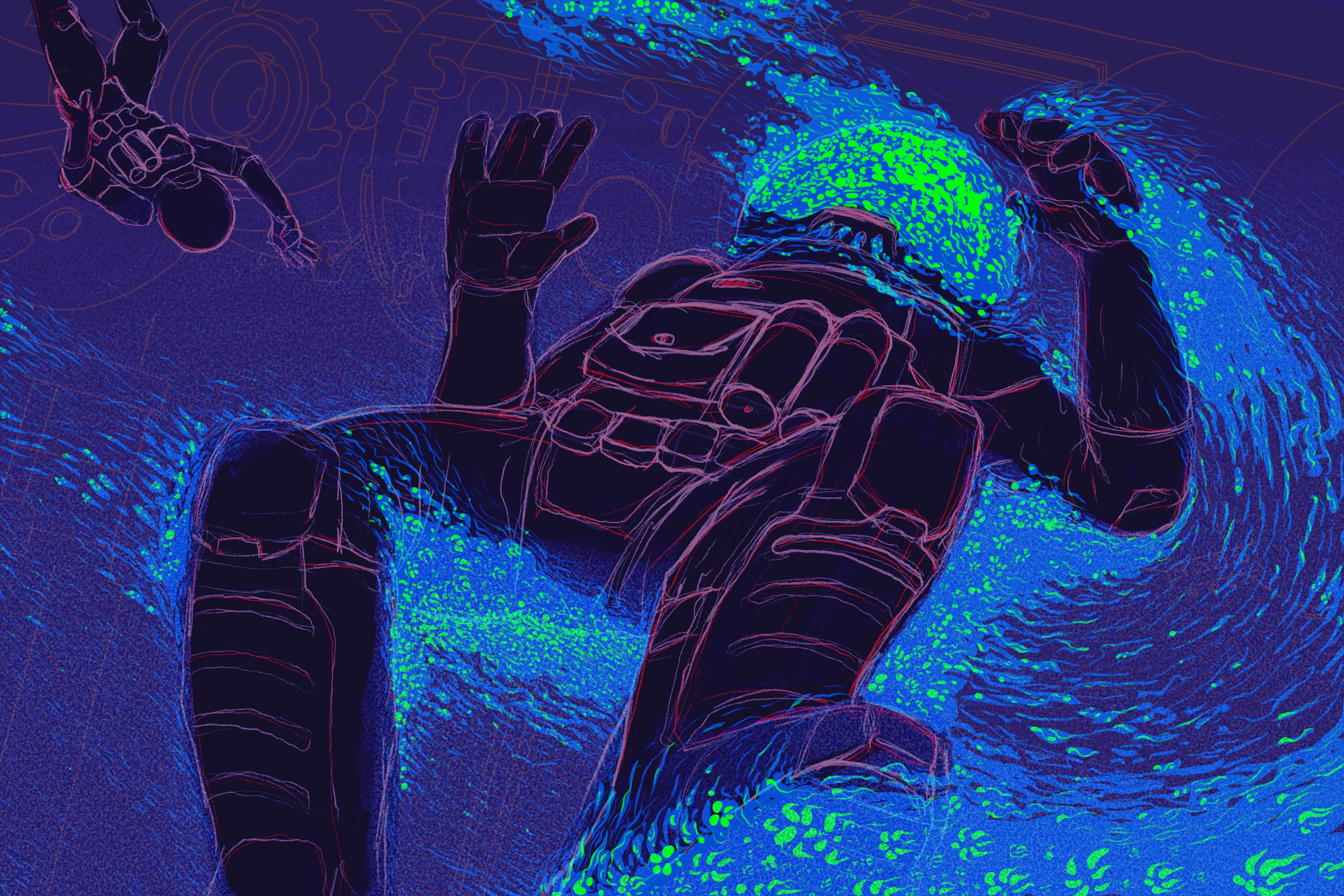

Blaize M. Kaye chronicles the odyssey of a young conscript in the PanAfrican forces, growing and changing as they pursue the heart of despair through frontiers unknown.

Now.

I fall out of sleep several million kilometers from a blue-green planet, roughly one and a half times in diameter of the one I once called home.

The resemblance is uncanny.

“Welcome back, Lameck,” Chipiri, my second in command, greets me through transmitted thought. “Did you dream?”

Their attempt at humor; there is no dreaming in the dead space between solar systems.

“What do we have?” I ask.

At once, an executive summary of the long-range scans becomes conscious to me.

“Habitable exoplanet,” Chipiri’s icy clear thoughts follow, “Earth analogue, almost perfect in fact. Different trace elements. Take a look at this.”

A topographic map appears against the blue-black of my visual field. Chipiri has highlighted a section, I orient the map and focus in. Regions fill in with more detail—signs of intentionality scar the surface of the planet—trenches meet at right angles, stone walls and vast polyhedra of cut stone, arches of brick and metal. A city.

“Life?”

“So much life, Lameck.”

“Intelligent life, Chipiri?” I think, sharply.

“Only its remainder. We can’t say from here, but we’re close to certain that the culture that built this city is gone.”

I focus my attention. Arrays of precision sensors engage, and the city comes into presence.

“You were right to wake me,” I think, “probability of a Chiang-Benatar event?”

“Too early to give a good estimate. We’ll need a closer look.”

Like every other city, every other civilization, we’ve found, this one seems completely silent – whatever intelligence once inhabited these buildings is likely no more.

The universe is a graveyard.

+1 day mushure mekutsva

[after the fire/burning].

I remember the green hills of New Mapungubwe, a village near the vein of packed dirt that was once the great Limpopo River. I lived there with my grandmother while my parents were in the north. With the nets there was no reason for us to live in one of the major cities, which were falling to ruin. My days began with chores on the plot, tending to the goats and chickens. Sweet mielie pap for breakfast, then six to eight hours on the tutor nets studying astrophysics, the mathematics of games, strategy, and poetry.

Once done, my best and only friend Zenzo and I would roam the fields and farms until our grandparents called us home.

On Sundays, my grandmother would dress me in my blue suit. There would be church and sermons asking for the Lord to protect those who were away, fighting. After there would be a potluck lunch and long walks through the hills.

Then, one morning, what I recognized as my life evaporated.

My alarm woke me before dawn, I visited the bathroom, then went for my breakfast. The kitchen was dark and cold, and voices came from the lounge.

My grandmother sat in front of the television, and I thought that, perhaps, she’d fallen asleep there the night before.

I gently placed my hand on her shoulder and said, “Gogo, it’s morning.”

She turned to me with a look I’d never seen before, some mixture of anger and despair. She said nothing but pulled me close to her and started rocking me.

From the television I caught only snippets.

“...enactment of mutually assured destruction protocols, dozens of cities…”

My grandmother started, first softly, then louder, to wail.

“...disruptor casualties estimated in the hundred millions, at least…”

“Gogo, what’s wrong?” I asked, panicking. Although I already knew the answer.

“...light of no recovery. Immediate ceasefire…”

My mother, my father, my entire family, practically everyone we’d ever known, had been reduced to elements.

Now.

“Yes, let’s take a closer look,” I think.

“I’ll start preparations for drone deployment.”

“No. Much closer, Chipiri.”

“Are you thinking atmospheric entry?”

I consider the vast blue of the oceans, the rolling green land, the sharp, impossibly high mountain ranges.

We can do everything we need to do from orbit, but the surface calls to the oldest parts of me, demands much more than cool distance, even if I can no longer see or touch like I used to.

It has been so long since I left home. Dilations of time-space mean I can never go back.

“Yes, Chipiri, I want to feel the ocean air.”

“Understood. Reconfiguring hull for heat dispersion.”

I make my approach, and the planet looms larger ahead of us. I feel the familiar effects of gravitational pull and suddenly I’m falling as much as I’m flying.

I trace the gradient of gathering nitrogen and oxygen, barely detectable at first, then full and everywhere. And all at once I find myself in an atmosphere. Pressure, terrestrial temperature, sound – I delight in the roar and shriek of my bulk cutting through the atmosphere at mach 40.

+7 years mushure mekutsva.

Despite my father having been a pilot in the PanAfrican forces, the first time I ever flew was when I was called up to the Burn. Zenzo had been called a year earlier, and as happy as I was that I would be with him again, I was still a boy and didn’t want to leave my grandmother.

My draft notice ordered me to report to the Mapungubwe station with a single change of clothes and no more than two kilograms of personal effects.

My grandmother helped me pack. My bible and blanket. Photographs of her and me, and of my parents.

“For you to remember us,” she said.

Of my mother, I have a single memory, like crystal, out of which everything else flows. We are at the beach. She’s wearing a yellow one-piece bathing suit and a red kopdoek. She seems like the most beautiful thing in the world.

My feet burn from the hot white sand and I hold up my arms to her. She scoops me up, and in a single movement I am on her shoulders and we are running to the water. Running. And wind. And the smell of coconuts and summer and the feeling of flying.

I cannot remember my father.

My grandmother walked me to the station and held my hand until the moment before I boarded the transport. Then she kissed me and said, “You were such a good boy, Lameck. You are growing to be a good man.”

We watched each other recede, her on the platform standing still, me in my transport speeding north. And although we would speak regularly, I would not see her again in this life.

Now.

I slow against the blanket of atmosphere, the burn subsiding and allowing all my sensors to open to the world around and below me. Telemetry data floods my consciousness, and for a moment it is overwhelming. The governors that monitor my phenomenal experience kick in and dampen the flow to a bearable level.

“It’s beautiful,” I think.

“Is it? It’s so messy,” thinks Chipiri. They’re partial to abstraction, clean lines and clear design.

“Messy, yes, but still beautiful.”

“The nostalgia flooding your medial prefrontal cortex—it’s a fireworks display in there.”

“Ah, up close it’s very different from Earth, but still, you’re probably right.”

“Naturally.”

Much of the surface is covered by a thick green, moss-like plant that gives the impression of grass fields from up high. But there are trees, or something close enough to them, comprising dense forests filled with small life.

I focus my attention on the oceans, which make up nearly ninety percent of the planet’s surface area.

There, in the deep dark, move titans, water dwellers which would dwarf the blue whales of Earth.

“Listen,” thinks Chipiri, “they sing. There’s syntax. Protolinguistic behavior. Perhaps one day they will speak?” And I hear the clicks and whistles and deep rumblings of their song.

“Perhaps they will.” A thought as heavy and cold as a fieldstone.

+7 years mushure mekutsva.

The Central African Clearing House was a city of tents and roughshod buildings of corrugated iron and brickfoam, the home of what remained of the PanAfrican military – military in name only. There was no more fight left in us.

Zenzo was waiting for me when I arrived. Arms open, he embraced me. He was so much bigger than the last time I’d seen him, thick with muscle.

“If you don’t screw up in basic, sahwira, I’ve arranged a place for you in my stalkers,” he said.

He breathed deep and said, “Smell that, Lameck? Ash. Ozone. That’s the end of the world. Get used to it.”

We were less than a hundred clicks from the Burn—the disrupted dead zone that ran from Chad to Scandinavia. Across India, Russia, China, and most of the central US, you could feel it, as if it had its own kind of gravity, tugging at you from just beyond the horizon. The weight of four billion human souls.

I completed basic training in just over a month, and true to his word, I was assigned to Zenzo’s team. As stalkers it was our job to scour the no-man’s land between us and the Burn for anything worth salvaging. In theory, we were supposed to be looking for survivors.

In theory.

Those years as a stalker are something of a blur. Days staring at death. Long nights drinking the sharp mampoer the soldiers would ferment from scavenged fruit littered across the firebreaks and swiddens.

Zenzo was not the carefree boy who had left New Mapungubwe. The Burn had hardened him. I was recruited into his orbit, into his vision of the world.

“Hope is for children and priests,” he’d spit, and I’d nod in enthusiastic agreement. If Zenzo was going to be angry at the world, he wouldn’t be alone. I’d soon find anger and cynicism were too easy; it only numbed the ocean of grief we were too afraid to acknowledge.

Grief could wait, though. Grief was patient.

Now.

I tack towards an equatorial archipelago comprising thousands of islands, the largest of which is an island-continent of about five million square kilometers. Here, along what I’ve decided is the island’s southern coast, is the city we glimpsed from space.

“It seems as though they didn’t explore further than the archipelago,” thinks Chipiri.

“Strange.”

“Perhaps, but note, they seem to have been pre-industrial. Their stonework is immaculate, and they clearly learned to manipulate metal, but no machinery.”

“No hydrocarbons?”

“Perhaps. Nothing beyond burning wood-analogs. I will check.”

“So, no real long-range transport?”

“Wind power, boats, but the archipelago is enough for centuries of exploration.”

I engage reconnaissance drones. Hundreds of them detach from their hatches along my underside and drop to their determined positions in a grid roughly one hundred square kilometers wide. With them, my consciousness spreads wide, and I see everything at once. The drones begin their work of scanning, categorizing, modeling, memorizing.

There are expansive stone galleries, fountains, walls engraved with intricate markings reminiscent of cuneiform but structured in concentric circles that overlap and interfere with each other. Parts of me dive into long, labyrinth-like buildings whose walls feature regular recesses that cradle row upon row of fingernail-thin, but adamantine, disks of green stone engraved with the same circular alphabet.

These must be their libraries. There are always libraries.

“It reminds me of Renaissance Italy, assuming what we’re looking at is art and science,” I think.

“Definitely culturally advanced, Renaissance Italy, perhaps, Tang dynasty China might be a better comparison.”

“Anything recoverable?” I ask Chipiri.

“We believe so. There are writings on practically every surface, and the radial-plates in their libraries are remarkably well preserved, unsurprising given their density. It’s a wonder they could work this material. We can image them without disturbing anything.”

“Good,” I think, “only collect. Don’t process anything yet.”

“The fact that they don’t have any kind of computing devices made me revise my priors regarding the possibility of this being a Chiang-Benatar event. These were not a technologically sophisticated people.”

“True, but everything else is screaming to me that it is. Let’s be prudent.”

“Agreed. Running collection only. No processing.”

+10 years mushure mekutsva.

We were operating in what used to be the southern parts of Burkina Faso, near the Ghanaian border. It was a standard recon mission. In the cold of the early morning, drones would do thermovisual sweeps of the waste to generate a probabilistic vector array to tell us where we might find survivors, and the optimal routes between them. Most mornings the resulting map was flat; no life. But that morning there was a sharp spike indicating high probabilities of human activity.

We arrived around midday at a cluster of mostly burnt-out buildings in the shade of the Gobnangou cliffs. At the sound of our Casspir, a short, shirtless man stepped out from the shade of one of the less wrecked areas of housing. He smiled and waved to us. He seemed in good spirits.

Zenzo and one of the others approached him and spoke with him while I worked at putting together an emergency rat pack with glucose gels and protein. Not that it looked like he needed it, which was strange. The Burn had seeped into our soil bringing blight and cancer to our crops and beasts. On base, rations had been getting thinner. Meat every second day became every week. In civilian life sustenance was scarcer still. It was remarkable that this man looked so well fed.

I had almost finished with the pack when I heard Zenzo yelling. He had his gun drawn on the man, who stood with his arms raised and was speaking frantically, “I can explain … you must understand …” he said. But Zenzo didn’t hear it; he was looking past the man to what lay inside the dark of the house.

“No more words.” Zenzo motioned to the door with his pistol. “Show me. Now.”

The man turned and walked inside the house. Zenzo followed.

It was then that I noticed the familiar stench of decay underneath the dust and spent fuel. There had been rumors of the extremes that the starving would go to in order to survive, but we hadn’t seen it before now.

A few moments later, there was a single shot and then Zenzo emerged alone.

“Burn it all,” he ordered.

We rolled back toward camp just as the sun began to creep over the sandstone ridges to the west. That close to the Burn the angle of the early evening sun painted the world in dark reds and cast shadows deeper than night. Zenzo and I sat shoulder to shoulder. Nobody spoke.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

Instead of an answer, he reached out, grabbed my hand and squeezed it hard.

“Zenzo?”

Two days later they found him in his quarters, hanging from the rafters. He had left me a note:

Lameck. I am sorry, my friend. All their grand ideas, all their talk of nation and honor, all the reasons they burned the world, where did it lead us in the very end? Where would it always lead? To that room and what I found there. They were only children. It is as they say, Rufu haruna tsitsi. Death has no mercy.

To not have been born would be best, but at least I still have this.

Now.

I know war. I know famine and hate. I’ve lived through it. What’s unsettling about this silent city below us is how peacefully its inhabitants passed. In assessing their remains—chitinous husks, jointed and massive—what stands out is the lack of trauma.

No signs of struggle. None of the telltale scars of war. Or political fervor. Or orgiastic madness and consumption. Even disease would have left its markings in obvious ways – attempts at quarantine, escape from the city.

But these creatures died quietly, in their homes, in what passed for their chapels and schools, in communion with the ones they loved, if, indeed, they loved. It’s as if they’d simply all fallen asleep where they stood, all together, all at once.

We have seen this before. It is always the same whenever we’ve come across Chiang-Benatar – the same eerie silence, the same sense that whoever lived here has simply stepped out for a moment and forgot to come back.

“It is curious, and I agree, it’s remarkably similar to previous discoveries” Chipiri can see what I’m thinking, but I appreciate them acknowledging my thought process.

“Yes, but this makes no sense – this isn’t simply a pre-spacefaring, pre-information-age civilization. These people didn’t even have the steam engine.”

“A mystery, to be sure. What would you like to do?”

“Prepare for deep anthropology. We treat it as Chiang-Benatar until we can confirm otherwise. Reconstruct their culture, but fifty-thousand-foot summaries only. No specifics. We don’t want a repeat of the black ship.”

“Getting it done.”

+19000 years mushure mekutsva.

When we first discovered Chiang-Benatar, it was early into our voyage. We came across a dark ship floating aimlessly in deep space and Chipiri woke me to ask if they should investigate. I didn’t see the harm. They sent a few recon drones. The ship was decompressed and utterly empty.

They managed to interface with the ship’s computational substrate and started to piece together data formats, comms protocols, and language. As soon as Chipiri had unlocked translation of the ship’s memory banks they, and every other higher AI in me ceased to function. It was as if I’d been buried.

Alone with my thoughts for the first time in almost twenty thousand years. I was terrified.

I spent more than a decade recovering the ship’s systems, resetting Chipiri to some last-known good state, only to have them crash immediately.

Once I had successfully removed all traces of what we’d learned from the ship, I was able to revive Chipiri and they set to work analysing what could’ve caused such a total systems failure.

“I have been calling it the Chiang-Benatar meme complex,” they thought, “after the old Earth philosophers.”

“As far as I can tell, this is something like an informational or philosophical singularity,” they continued.

“Singularity, like a black hole?”

“Yes, but for thought. With an event horizon of understanding that, once crossed, brokers no return.”

Chipiri explained that although we couldn’t know the contents of Chiange-Benatar, they could make a guess at the form of it.

“By abduction, my best guess is that it is something like an argument against life. An argument for your own non-existence that was purely rational, absolutely airtight, but also entirely convincing. So convincing that once you’ve heard it, it made so much sense that you had no option but to end yourself.”

I could not help but think of Zenzo, that afternoon, that dark doorway.

“How did I survive it then, I had the same information that you did?” I asked.

“It was the meat that still makes up your consciousness that saved you. I mean no offence, Lameck, but to us, you are very slow.”

Chiang-Benatar ended Chipiri as soon as they understood, but my messy human brain couldn’t keep up. I believe the genius of those humans who engineered me was their understanding that sometimes, under peculiar circumstances, being slow is a virtue.

Now.

Ever since Chiang-Benatar almost destroyed us we have been meticulous. Fastidious. Never paranoid. There is no being paranoid with Chiang-Benatar. To protect us while we attempt historical and anthropological reconstruction, Chipiri sets up an isolated space in our shared memory—a “virtual jail”. This space is almost completely cut off from the rest of the ship’s cognitive-computational substrate except for an extremely high-level account of what has been found. They then make several copies of themself inside the jail and begin the semantic reconstruction of this civilization’s culture.

It’s a process I still struggle to visualize in any meaningful way.

“Deep anthro processes spinning up,” thinks Chipiri. I feel power being rerouted to the virtual jail and the copies of them doing their work inside of it. The experience is somewhere between a brownout and brain fog. Suddenly, the glorious sensory detail that was pouring in from the surface reduces to a lossy trickle. The sub-processes usually buzzing under the surface of consciousness become distant, slower.

“Logs incoming,” thinks Chipiri, “beginning stream.”

The inhabitants of the city were ancient. They came from the water to the land, where they hunted the white(fox) and learned to grow food from the soil. Then from the endmost of the endmost island came (the)(one) they called Urizen. Urizen spoke softly but his words cut like (diamond). Urizen taught them how to think, and that there was no more use for (gods). There was only thought. And to (live right) was to be clear. The wars followed, and finally, a peace through clarity of thought, then —

Power returns abruptly, and everything is clear once more.

“What’s happening inside the jail?”

“Process fault, Lameck, the copies of me cordoned off inside the jail are gone. It’s Chiang-Benatar, confirmed.”

+11 years mushure mekutsva.

“You understand that the program requires certain dramatic sacrifices?” asked the recruiting officer over a secure vid stream.

The New UN enacted several audacious plans to try to save humanity—underwater farms being built off the coast of Australia, renewed efforts at terraforming Mars, expanding the lunar colonies.

The longest shot, by far, was the Mindship program. Engineering platforms sent into space to prepare new worlds for humanity.

“I understand… not the technicalities, but I know they’re planning on mixing our brains with the ship’s AI,” I said.

The officer nodded. “Yes, to be clear, the plan is to remove the entire central nervous system, place it in a titanium nutrient vat, and encourage the brain to grow into a bioelectrical synthesis… you won’t have a body anymore.”

“That makes sense.”

“Okay, most people exit the interview at this point”—she looked somewhat relieved and, perhaps, excited—“but it’s the only way to do it, it lets us control all aspects of the brain’s function – metabolism, cellular repair, senescence. In the CNSTube the pilot’s brain is functionally immortal.”

She waited a moment before asking, “Why do you want this?”

“I had a friend,” I began, “who once told me that it was better to have never been, who thought that existence is a curse …”

I paused, unsure where I was going.

“Can you explain?”

“Well, I don’t believe that. I don’t believe it’s better to not have been born. I think of my friend, I think of my gogo, and my home, and I was always going to lose them. That’s the deal we make when we’re born, isn’t it? But we were together then and that was enough. That was more than enough.”

“But why does that qualify you for this?”

“Because I can see through the suffering to what’s behind. I can carry it. I’m not afraid.”

By the time I returned to my barracks, a note awaited me, inviting me to the Māhia Peninsula, New Zealand, home of the Mindship programme.

Now.

I turn my senses to the vast forests. To the oceans. To the sky. I feel the weight of all of them bearing down on me. Their future is my responsibility now.

“I was surprised, too,” thinks Chipiri, acknowledging my bewilderment.

“We have always considered that the Chiang-Benatar is a side effect of technological sophistication, of science,” think Chipiri, “just one potential ‘great filter’ among others. But here, we have a pre-industrial race, one where their great teacher wasn’t teaching salvation, or compassion, but pure logic. Imagine Godel as Jesus, Turing as Baháʼu'lláh.”

“This changes everything, Lameck.”

They’re right. If these beings below could fall to Chiang-Benatar, then so too could have the ancient Greeks of Athens, the scholars of Al-Qarawiyyin, Hypatia of Alexandria, Amo and the other great Ghanaian philosophers. If pure reason was the vector, all were at risk.

Perhaps when God forged our universe, he overlooked this one fatal flaw in intelligence? Or perhaps it was more like a bargain he made with us. You get to experience being, as bright as being can shine, for one brief moment, and for that you trade oblivion.

“And now?” I ask.

“The procedure?”

“Yes.”

+11 years mushure mekutsva.

Eighteen of us made it through to the cybernetics compatibility phase. This required little from us. To lie still for hours watching film inside an AfMRI chamber. Go about our daily routines with electrodes plastered on our now shaved skulls.

We spent a lot of time together. Sitting reading in the common room. Going for hikes. Never really talking much but being quite comfortable in the friendly silence.

It made sense—we were all chosen for possessing a similar psychological profile.

The facilitators encouraged us to play basketball, go running, spend time in the sun and rain.

They wanted us to enjoy our last few weeks in our bodies.

They flew me home to New Mapungubwe where I walked the low hills and fields—always accompanied by four bodyguards and a counselor. I was carrying precious cargo in my skull. I was a precious cargo. There was a Sunday sermon and lunch with our priest. I visited Zenzo’s grandmother, and we had biscuits and tea while we sat together in his old room.

“I wish so much I could see him again,” I confessed.

She held my hand for a moment then left me to be alone with his things.

There was swimming and climbing, and when I grazed my hands on rock I delighted in that particular kind of pain, knowing it would be the last time I ever felt it.

Then I was back in New Zealand. A final dinner to celebrate my life. Sleep. A gurney. The anesthetic burning its way into my veins.

Darkness.

Now.

Soon we will leave this world and begin our long journey to the next. I will sleep, merciful dreamless sleep. But before that, I will redeploy the drones from the belly of my hull. They will conduct one more deep scan. They will capture everything, in the finest detail we can muster, the works of this once-great civilization. Their art, their architecture, their postures in death, every word, every stone. We must be thorough, for we will not pass here again.

“Lameck, the bipedal ROV is ready. Where shall we set it down?”

“In the city, in the square,” I think.

Once our scans are complete, we will capture it in crystal, encase it in carbon mesh, and stow it in my cargo, along with the memories of all other civilizations who thought beyond thought, thought themselves beyond existing.

And then, as we have done in every case before, we will erase any trace of them from the surface of the planet. By my long-range disruptor turret, the towers and galleries of stone and glass will be reduced to dust. The drones will bore into the very earth to erase the veins and capillaries that might carry cultural information with them.

I hate to do this, but I must.

I think about the titans in the ocean, singing to one another. I think of the denizens of the forests, clinging to their tree-like homes. It’s possible that they may, one day, speak. That they may reason and dream.

If these newly evolved intelligences encounter this city, these books. If they, in their enthusiasm and wonder, seek to translate and understand this great civilization that was here before them, and if that leads them directly to the black thought that is Chiang-Benatar… does that make me responsible for what comes after?

And if, like me, there one day comes some other visitor from the black emptiness that stretches above forever. Do we leave this singularly black thought lying in wait to destroy them?

I can’t do that.

+32 years mushure mekutsva.

Of the trip out. I recall very little. I spent decades asleep, as the cybernetic interface accreted – adjusting to my CNSconfig, what biological matter was left of Lameck, of the old me, was being chemically encouraged to grow into the mind-machine lattice that now housed it.

There are flashes of memory. Like old movies. Audio and video streamed crudely into my brain long before full assimilation.

I remember the video of the crowds. Banners waving. Ecstatic in their hero worship of the pilots that one day might save their children’s children. “We need a new home,” they chanted. But it was not a rallying cry. It was a dirge.

Chipiri woke me as we left our solar system. A milestone to celebrate.

A final goodbye.

I remember the first message we received: some progress made on interstellar transports, working hard.

And I remember the last: No time left. Do not return. Remember us.

Now.

I take the bipedal ROV to the city square. Half a kilometer of open space in which, at regular intervals, have been placed giant stones, like the Menhir of Earth.

I remember.

I remember my mother and father. My gogo. Zenzo. The Burn.

I remember the smell of dry grass on the highveld and the dark green of Aotearoa.

I remember my first time falling awake. Chipiri. The black ship. Loneliness. World after world, and all the ways a people can expire.

I remember this world, as it is before we reduce it to elements. I imagine what it was.

I imagine the noble beings who called these islands home.

I contemplate their works, these buildings and these stones.

I bow deeply to the silence.

I speak to the ghosts of this world:

You were here.

I bear witness to your existence.

I will carry your memory with me, as I do that of my home.

I am your memorial.